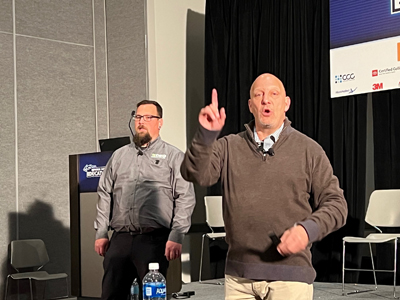

Prove It

Use OEM repair procedures; estimating systems; credible internet sources like SCRS, I-CAR, ASE and OEM websites; manufacturer bulletins; scan tools; the vehicle manual; DEGweb.org; and Collision Advice’s “Who Pays for What” surveys to find documentation supporting your position.

SCRS’s Guide to Complete Repair Planning, available on SCRS.com, is a reminder of steps that may be performed during repair process, Anderson said, and the SCRS BOT, available at scrs.com/bot, finds potentially missed line items.

“The average shop that uses this increases estimates by $300 to $600,” Anderson said.

Gredinberg said the DEG allows shops to submit inquiries about steps and parts that might be missing from repair procedures in CCC, Audatex and Mitchell. The inquiry is usually resolved within a day, and the procedure gets updated.

Anderson said to build a foundation of trust with the insurance providers as well.

“A foundation of trust gets to resolutions quicker,” he said. “You can have an honest dialogue without fear of them judging you or getting mad.”

When an insurance provider says no, it doesn’t mean no---it means they don’t know enough to say yes, Anderson said. “They’re not convinced.”

Use time study videos---recording a technician performing a step in the repair process---to prove how long it takes and how much that labor time is worth, or a resource like 3M’s RepairStack.

Next, focus the conversation on what the negative consequences will be if you do not perform the operation.

“Tell them, the reason I need to do this is because if I do not, these are the negative consequences,” Anderson said.

As an example, he said, Toyota says when the bumper is removed, the front camera must be adjusted, because, if not, the panoramic view monitor system won’t work.

If the insurer doesn’t want to pay for the front camera adjustment, ask “How should WE notify the vehicle owner the panoramic view monitor system won’t work?” Gredinberg said.

Next, try to understand the insurer’s position.

“You don’t have to be wrong for me to be right and vice versa; there can be two right answers,” Anderson said. “It’s all about perception. Why do they believe they should pay for four hours on that dent when you think it needs a new door?

“Seek to let that person feel like they’ve been heard,” he said.

When adding a new charge to an estimate for the first time, the appraiser will ask “Why now?”

“Start the conversation with your story---what has changed in your world,” Anderson said. “You took a class, watched a video, read an article, saw it in the owner’s manual, etc. Have the documentation ready before they arrive.”

Anderson said the goal is to present your estimate so matter-of-factly, “no” is not an option. He suggested improving interactions with insurers by developing scripts and practicing those conversations with your team, after business hours, a minimum of four times.

Avoid the “pause” in a conversation with an insurer, Anderson said.

“It causes you to second guess yourself and then cut your own estimate,” he said. “Instead, go straight in to presenting the facts, and close with the negative consequences [of not performing that operation.]”

If the insurer still is not convinced, the options for the repairer are to perform the operation for free, charge the customer, refuse the job, ask for a hold harmless agreement, right to appraisal, involve the agent or have the customer come on-site and meet with the insurer, but prep the customer first.

“The best thing you can do is to get that customer involved in the very beginning,” Anderson said.

“At the end of the day, remember: do you want easy, or do you want worth it?” he said. “This is not a magic bullet, but it’ll increase your chances of reimbursement.”

Abby Andrews